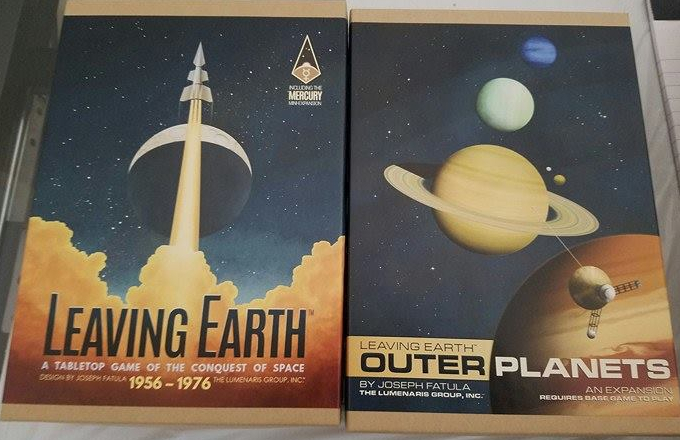

Welcome to the first tabletop game summary/review I’ll be doing here. Over the last few years, I’ve really gotten into these games and have amassed a bit of a collection. Once a month, I’ll be plucking a game off my shelf and doing a review. This week’s entry is going to be Leaving Earth by the Lumenaris Group.

Leaving Earth is set during the Space Race period of history. You’ll choose a space agency, construct the solar system, research your technology, and complete missions. All of these are represented by tiles and cards, and you have little wooden pieces to represent your vehicles as you move them through space. By default, Leaving Earth now includes the Mercury expansion and thus covers the inner solar system: Mercury, Venus, Earth, the Moon, Mars and its moons, and the asteroid Ceres. Outer Planets adds, unsurprisingly, the outer solar system as well as some new mechanics.

First: quality of components. Everything in this game is really well-made. I initially had some concerns that the planet tiles and component cards would be flimsy, but they’ve held up really well through a couple plays. There’s wood tokens to represent spaceships, capsules, and satellites that are color-coded to match each space agency. The game is just really well made.

But how does this actually play? Well, you start by laying out planet tiles to build the solar system. Then you choose the “difficulty” of the game and lay out a number of missions that range from Easy to Hard. The missions I don’t want to spoil too much of, but they range from “survey the Moon” to “land a man on Venus and return him.” Harder missions take more time and are more difficult to complete, but they earn you more points. The missions are public, and once it has been completed, nobody else may complete that mission.

In order to build your ships to complete missions, you must research Advancements. Advancements are things like Atlas or Saturn V rockets, capsules, landing technology, or even ion thrusters. You’ll receive an Advancement card, and you’ll put a number of Outcome tiles on that card. Every time you use the Advancement by, say, launching a rocket, you’ll flip the top Outcome tile. Outcomes are Success, Minor Failure, and Major Failure, and the Advancement card instructs as to what each Outcome means. This represents how you test and learn about technologies.

At heart, Leaving Earth is a game of risk management. You’re given $25 million space-bucks at the start of each year. You can never earn more, and you don’t carry over money from the previous year. So each year, you only have $25 million to spend on Advancements and components. But, you can also pay to remove Outcomes from your Advancements as well. $5 million erases a Failure, and $10 million buys off a Success.

Buying out Failures is obvious, but why would you buy out a Success? Again: risk management. You may draw a Success and shuffle it back in. Then draw it again. And again. Now you’re feeling pretty good about your expensive rockets, but do you really have all Successes in your Outcomes, or have you been getting really lucky? Buying off Outcomes reduces the chances of having something bad happen to your spaceships, and when no Outcomes remain on your Advancement, that component will always be successful. It’s up to you how you spend your money, but buying away Outcomes can be the difference between your ship making it to its destination or exploding in the last leg of a journey.

The game simulates rocket science and physics with a small formula so do know the game can get somewhat mathy. Moving around the solar system requires what the game calls Maneuvers, and each Maneuver has a difficulty rating on the planetary tile. Each component card has a Mass rating in the corner. You’ll add up the Mass of every component then multiply it by the Maneuver’s difficulty to find the required thrust to complete. For example, going from Earth to Earth orbit has a difficulty of 8. If your ship has a total mass of 10, you need a minimum of 80 thrust to complete the maneuver.

As you might guess, the game can be a bit of a brain burner. Longer, more complex missions require more components and more math. It’s a game where you have to work backwards: you’ll have to choose the mission you want to complete then work toward that. And due to the budgetary restraints, you’ll often spend turns just scribbling some notes and buying components for a future mission. Be warned, too, that this game takes up an enormous amount of table space. I’ve often called it more an “experience” than a game proper.

Part of the reason is that the game’s competitive variant is…a bit weak. There’s very little player interaction, and per the rules, when one person completes a mission, everyone else gets $10 million immediately and the chance to spend it. This means there’s no real incentive to go for low-point missions because you funnel money to your opponents to complete bigger missions. Instead, I often play it as a coop game where each person has a role and run by solo play rules. Agency Director decides which missions to pursue and how to appropriate funds. R&D figures out which Advancements are necessary. Rocket Scientist handles the math to figure out how much thrust is needed at each step. The goal is to acquire more points in completed missions than points are left on the table when the game ends after 20 in-game years.

Overall, having played Leaving Earth solo and coop a few times, I’ve enjoyed it. Again, it’s kind of a heavy, brain-burner game with a lot going on. But if you’re looking for a space research game with a retro aesthetic and a good theme, then I found the base game to be worth the $40 I spent.